- Home

- Thompson, Ted

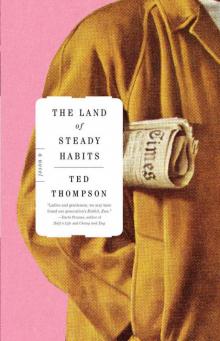

The Land of Steady Habits: A Novel

The Land of Steady Habits: A Novel Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Newsletters

Copyright Page

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For Kip and Delia

Part One

1

One of the great advantages of Anders’s divorce—besides, of course, the end of the squabbling and the sudden guiltless thrill of freedom—was that he no longer had to attend the Ashbys’ holiday party. Their party, like all of the parties he’d attended in his marriage, was his wife’s domain, and he was relieved to no longer have to show up only to be a disappointment to her friends. In fact, the Ashbys’ holiday party had become a sort of emblem of obligation to Anders, a reminder, at the end of his marriage, of the kind of man he’d become, when at last year’s party, after three quick whiskeys and a squabble with Helene about their grown children, he’d turned and announced to the room that they hadn’t had sex in five months, and, even though he was over sixty, it wasn’t because of his penis either.

The amazing thing, though, was that after all that, after it was clearly his decision to end the marriage; after he’d left what her friends saw as a perfect woman for a life in a condominium, retired, pretty much alone; after he’d openly scorned them and was sure she’d revealed all of his dirtiest secrets to them over brunch, a card arrived from the Ashbys, as if with the season, inviting him once again to their holiday party.

They held it every year in the week after Thanksgiving to get a jump on the season and, he’d always thought, to claim it as their own. It was the only invitation he’d received, so he brought it inside, set it on his small breakfast table, and ate dinner across from it, staring at the familiar handwriting, the Santa Claus stamp, trying to decide if it was a peace offering or if they’d simply forgotten to take him off their list. Divorce, he’d learned early on, was not so much from your spouse but from all of the things you’d forged as a couple—the home, the parental authority, the good credit, the friends. He pictured Helene in her elegant party clothes holding forth in the Ashbys’ kitchen—a brave single woman in a chenille scarf who, after a year of injustice, maintained the dignified poise of a survivor. She would be an honored guest there, a woman who’d spent her career helping adults learn to read and was now forced to face the season alone.

The invitation was stiff and glossy—a photo of the Ashbys in front of their tree. It’s That Time of Year was all it said, as though if you were receiving this, you had been for twenty years, which, Anders realized, was about right—twenty years of enduring this soiree, and still, after he’d thumbed his nose at the lot of them, after he’d announced to Helene, in the heated mania of a bedtime fight, that the stench of Mitchell Ashby’s cigars made him wish he’d been born without a face, he’d been invited. He placed the card on his mantel, the Ashbys beaming down at him in cable knits, and settled below them onto the couch.

There was also the issue of the other piece of mail that came that day, a product of that final meeting with the lawyers, when Helene had shown up with a firing squad of attorneys and asked him, without warning, if she could keep the house, and in a moment of regrettable pride, though it was half his net worth and carried a disastrous second mortgage, he’d told her of course she could. Or, as his attorney reminded him, he’d implied she could, after she’d implied in front of all those men and women of the law that he’d been anything but a man of responsibility. What he’d actually done was put his palms on the table, lean toward Helene and her posse of lawyers in rimless spectacles, and say, “The house? All you want’s the goddamn house?”

The trouble was that he had planned to use the money from the house to pay for his early retirement. He could afford the house or he could afford to retire, but he couldn’t afford both. This put him in the uncomfortable position of having to admit to Helene what had become her biggest grievance: that he had chosen himself over everyone else, that he had thrown them all under the bus. Which wasn’t true. Which, if you considered the college educations of their grown sons and the house he had mortgaged up to his eye sockets and the extravagant kitchen she had insisted on building after their children were gone, all of which he had paid for, all of which he had worked his rump off to provide for them—his family, his brood, his paramount responsibility—was downright insane. He had done everything they asked of him, and he had done it for them. What else in the world could she possibly want?

Well, the house, as it turned out. So now the letters were piling up, ominous things with yellow forwarding stickers over the address windows and language that was quite explicit: he had until the end of the year before the bank brought in a judge. It was a situation that could be cleared up with a single phone call to Helene, an opportunity, really, to come clean and admit he’d bluffed—the right thing if ever there was a right thing—if he could just find the moment when she wasn’t so fragile and he could stomach her disappointment in him, when it didn’t feel like a single piece of bad news might be enough to send her away for good.

What it all meant, at least in terms of the Ashbys’ holiday party, was that he should probably have a shirt cleaned.

* * *

As it was his first party as a single man, it surprised him how cordial he could be, how confident, crunching alone up the Ashbys’ wide, candlelit path; nodding at some acquaintances as they passed him; removing his coat and hanging it on the rack and turning to a room of rosy faces, their chatter rising over Harry Connick Jr., voices familiar; making his way across the living room, past the mantel full of teepeed cards, his eyes falling across their handsome photographs—a golden retriever, some newlyweds, a ten-year-old in a soccer uniform.

Before he could get to the bar, Lydia Hickman had spotted him and was motioning eagerly to have Anders join her. Lydia had been an intimate member of his wife’s support system during the divorce—a coffee-getter who had been through two divorces herself and who, Anders always imagined, had strong opinions about the incompatibility of men and women. She was standing with four others, some of whom Anders had met before but couldn’t recall where.

“So how have you been?” said Lydia, her eyes wide.

Anders glanced around the circle of faces. He was the first of his peers to retire, and he could feel he was being tested. The truth was he had proceeded as planned—selling his unneeded furniture, buying a condo and a decent TV, repainting, getting his green square of lawn ready for spring. The truth was he enjoyed his time alone, his three mugs of coffee during his morning shows, his lengthy shower, the long daytime hours of walks and mail and raking. “I’m getting involved with charity,” he said.

“Wonderful,” said Lydia. They waited for him to continue but he had a moment of self-awareness and couldn’t.

“Which one?” someone asked.

“Disease,” he said. “Cancer.”

Lydia nodded gravely and a strange silence fell over them. That word had a tidy way of ending conversations.

“So what do you do?” said a man. He wore French cuffs and a tie with a muscular Windsor. Anders could feel him angling for familiar cocktail banter, the sort of sniffing of butts that he had sworn off with his retirement.

“He’s retired,” said Lydia.

“Oh,” the man said. “Lucky dog.”

“From Springer Financial,” she s

aid.

“Oh,” said the man. “You left Springer? I mean, you’re still young. Aren’t you?”

Lydia, intrigued, turned to hear his answer to this one.

“Am I young?” said Anders.

“Yeah,” he said. “I mean, it’s early, isn’t it?”

This was the topic his older son had coached him to avoid, the one he’d sat Anders down in the weeks immediately following the divorce and, as if in an intervention, begged him not to broach in public. “Even if everything you’re saying is true,” Tommy had said, “you can’t rant. It makes people uncomfortable. You seem…”

“Crazy? Is that the word you’re looking for?”

“Assholey.”

But the tirades came out of him, like the lie about the charity had, in ways that at first seemed appropriate. They had asked him about his retirement, his career, his decisions, hadn’t they? They wanted to know why he had turned his back on a life that was so similar to theirs. And so out it came: the reddening of his face and the raised volume of his voice, the mounting extremity of his language.

“The guys at the top are crooks,” he was saying to Lydia and her inquisitive friend. “They’re not in it for the client, they’re in it for themselves. And let me tell you something, Paul, they have to be. That’s become the industry—save yourself, outsmart the other guy, don’t worry about the consequences. That’s the corporate ethos and if it doesn’t make you sick, you might want to think about having your head examined. Because it’s not just the banks, it’s everything, Paul, it’s a system of monstrous greed—and for what? More toys? Bigger houses? Trips to the goddamn Caribbean?”

It wasn’t really him, Helene had said after a similar outburst at last year’s party; it was like a child throwing a tantrum. If he actually listened to himself, he wouldn’t be able to follow it. First the problem was the banks, then the lawyers, then their town, then every single person who lived there. Nothing was spared. It was all scorched earth. “I just don’t understand where it’s all coming from,” she had said. “It’s all so extreme.”

“I’m not going to hide how I feel.”

“Anders, you hide your feelings about as well as an infant.”

“So I should just be like Mitchell, is that it, buy myself a giant boat and join that conversation about bilge pumps?”

She shook her head. “I don’t understand why you’re so unhappy. I mean, look at yourself—what could you possibly want?”

This, of course, was exactly it—even when he’d calmed down and could think with a clear head, he had no real answer. The question was more like, What did she want? They had two boys with impressive degrees, and grandkids who went horseback riding. His bonus last year was more than he’d made in his first decade at work. Were they supposed to become one of those couples who travel all the time and send Christmas cards of themselves on camelback or, worse, buy a condo in Charleston and fill it with art? It must be terrible, she’d said that night in bed, to do everything right, to play the game so by the book and still find yourself unhappy. Maybe he should talk to a professional to figure out where this was coming from. Maybe all this anger was just rooted in the fact that he was confused.

“Confused? What could that even mean—confused? Confused about what?”

“Honey, it’s a nice way of saying ‘fucked up.’ ”

When he finished talking, he was out of breath, and Lydia Hickman was staring into her wine. It was a moment Anders knew well, so he also knew his audience would split off in different directions—for the bathroom, the bar, another more urgent conversation—and as they did, he stood alone, drinkless, listening to the shrill cheeriness around him and searching for a way to quietly escape.

Which was when he saw Monster, the Ashbys’ bushy golden retriever, curled on the back deck. There was his excuse—go out, pet Monster, and slip away to his car. He found his parka on the rack and grinned mildly at anyone who caught his eye as he made his way through the sliding glass door and into the icy evening air. When he’d closed the door behind him, he heard giggles from beneath the deck and an urgent whisper: “Guys, guys, someone’s here,” followed by a waft of reefer so potent it nearly made his eyes water.

Anders leaned over the railing to see the shadow of three prep-schoolers with shaggy and terrible hair. They reminded him immediately of Preston, his younger son, whom they had sent away to St. Paul’s for the individualized attention but who had come home each Thanksgiving and June taller, more unkempt, more broodingly silent, his face a puffy red mess. It wasn’t until his senior year, when the school discovered a four-foot bong in his room and tossed him, and Helene insisted they check him into a rehab facility against his will and search his entire room for clues—reading his old love letters from camp, his yearbook inscriptions, and finding only one unopened box of aging condoms—that Anders realized his failing as a father: it wasn’t that he couldn’t provide, for he gave his boys everything; it was that he knew nothing of them, nothing of their internal lives, and though he was their sole male role model, doling out advice each week over the phone, he had never even attempted to ask.

The boys held their hands behind their backs and pretended to be cool.

“Yo,” said one of the boys from the shadows. “What’s going on?”

“Just getting some fresh air. It’s warm in there.” They all nodded as if Anders had said something very wise. “What are you guys smoking?”

They froze. One toed the gravel.

“Relax, I’m not going to tell.”

“Seriously?” said the tall one in the middle. “Because if you’re one of my dad’s friends who he sent to narc on me, then you can go back and tell him he’s really predictable and sad because we were just looking at the constellations.”

“Charlie?”

There was a pause. “Who is that?”

“It’s Anders.”

The boy stepped forward from the shadows, squinting. “Christ.”

“Look, don’t worry. I’m not one of your dad’s friends, first of all, and second of all…” He couldn’t think of a second of all. The first was true, and he had surprised himself with it: What else did the kid need to know? “Anyway,” said Anders. “Enjoy your constellations.”

“Wait, dude,” said Charlie. “Come down here for a second.”

Anders went down the stairs and onto the dark packed dirt beneath the deck. The boys were taller than he’d thought, all of them meeting his eye.

“You know me, but that’s Arnie and that’s Gorbachev,” he said, fiddling with something that looked like a small, deflated basketball. “So what d’you mean, you’re not friends?”

“I’m not. I mean, I was. And my wife is. Ex-wife, sorry. She’s their friend. I can’t stand them. Really, I find your parents unbearable.”

Charlie let out a laugh and went back to the thing in his hands—a mini-pumpkin, it turned out. After a moment he glanced up again. “Seriously?”

Helene had met Sophie Ashby in a prenatal fitness class, five strangers in the shallow end at the Y doing a workout so low impact, she called it “manatee hour.” When the babies came and Helene found herself with two tyrants in diapers and the demands of a career, it was Sophie who, according to Helene, kept her from losing her mind. They started a playgroup, trading off tantrum duty and daytime PBS, and by pre-K, carpool drop-off became a respite of coffee and chitchat, and on Fridays a splash of wine, with Sophie indulging in two drags of a cigarette before stubbing it out in a potted plant while the kids ran rampant and Helene savored the thirty minutes that she was responsible only for her shiraz.

By the time Charlie came along, thirteen years after his sister, Samantha, the children of the playgroup had retreated behind the closed doors of their bedrooms, and all the hand-me-downs had long ago trickled to Nicaragua. Although everything about Charlie’s birth appeared to be an accident, he was, in fact, a miracle of progesterone and planning, a little bundle of joy born to a woman of forty-four and into her circle of love-star

ved friends. He was passed around for babysits and his bassinet was given a space at the table during dinner parties, where he was as quiet and pleasant-smelling as a candle. When Samantha became Sam and buzzed her hair and had a bar jammed through the soft skin under her lower lip, Charlie was in the Cub Scouts with an adorable little neckerchief. And when Sam moved out to Seattle—always too poor or too busy to fly home; likely a lesbian; even more likely a vegan; her only regular communication with her family the poorly copied issues of a magazine she’d created, a jumble of cartoons and words that bled right off the page that neither Mitchell nor Sophie could make any sense of—Charlie would sit on the sofa in the living room and regale dinner guests with an impersonation of his gym teacher, his legs crossed exactly like his dad’s.

To say he was spoiled wasn’t quite right—he was simply given everything: a Gameboy he bowed his head to at the restaurant table, and sneakers with wheels embedded in the heels. And when those things failed to please him, his parents capitulated and bought him a box turtle that they knew would live forever and that he used to set loose at inopportune times so that, at least once, a dinner guest was sent shrieking from the bathroom.

“You know how to rip one of these?” he said, holding up the pumpkin. There was a Bic pen jammed into the side of it and a trough hollowed out that he’d filled with pot.

“I don’t even know what that is.”

“This,” he said, “is resourceful.”

Curiously enough, the last time Anders had participated in this ritual was several years ago on a vacation he and Helene had taken with Charlie’s parents. Not four hours into their stay in a Costa Rican villa, Mitchell Ashby had produced rolling papers and a dime bag to go along with the afternoon tea. The vacation, it seemed, gave him permission to revert to the habits he’d formed in prep school, habits he’d had to give up with their firstborn. Anders had felt as helpless then, when he was asked to roll the thing and spilled most of the delicate leaves on the glass countertop, as he did now, with the contraption held in front of his face and his new friends staring at him with calm expectancy.

The Land of Steady Habits: A Novel

The Land of Steady Habits: A Novel